- Over the past eight years, US economic growth and real wages have underperformed expectations, yet the stock market has tripled in value.

- Since Q1 2009, nominal GDP has been up 31% (17% in real terms), real wages have picked up less than 1%,

- One could argue that central bank policies are socially non-optimal in that they reward those who are well off (people who have the ability to buy stocks and/or real estate) at the expense of those who are savers (retirees, conservative investors) - who now make little to nothing off interest - and those unable to invest in risky assets due to a lack of disposable income. Widening income disparity can breed social conflict and could be at least be partially attributed to the surprising electoral outcomes of Brexit, Trump, and possibly additional unanticipated results in the upcoming European presidential elections in France, Germany, the Netherlands, and potentially Italy.

Summary

Over

the past eight years, US economic growth and real wages have

underperformed expectations, yet the stock market has tripled in value.

Main influences include an initially oversold market in 2009, central bank policies, and heavy credit expansion at the corporate and government level.

The market’s current price point suggests an overbought market with risk skewed to the downside.

However, a continuation of negative real rates and additional credit expansion may continue to provide for a bullish short-/medium-term outlook.

Main influences include an initially oversold market in 2009, central bank policies, and heavy credit expansion at the corporate and government level.

The market’s current price point suggests an overbought market with risk skewed to the downside.

However, a continuation of negative real rates and additional credit expansion may continue to provide for a bullish short-/medium-term outlook.

Argument:

The past eight years have provided one of the best bull markets in

history despite one of the weakest expansions out of a recession in

history. It's my belief that the US equities market, taken as a whole,

should be avoided from a value perspective, although I recognize that a

continuation of low rates, further credit expansion, and earnings growth

from upcoming fiscal measures could continue to support higher

valuations.

Overview

Since Q1 2009, nominal GDP has been up 31% (17% in real terms), real wages have picked up less than 1%, yet the S&P 500 (NYSEARCA:SPY) has tripled.

If this article were to be delayed until the second week in March, and

the S&P 500 stays at its current valuation, the rise over the past

eight years will come to a factor of 3.4x - 240%, or 16.5% annualized.

This compares to 3.4% annualized in nominal GDP appreciation, or a

spread of about 13%.

This is a massive discrepancy

that shows that the rise in the US equity markets has been a product of

far more than basic economic growth. Some contributing factors:

1. The S&P was oversold when running below 700 in March 2009

Markets

tend to oversell in times of panic. Fear is a stronger emotion than

greed, and losses tend to hurt far more than gains from a psychological

perspective. Investors pulled their money out of funds in record

quantities and were far undercapitalized when there was a grand

opportunity to snap up many highly underpriced assets. Even though the

crisis was mostly cleaned up by the end of 2008, the market continued to

sell off for another 10-11 weeks after before starting to reverse

course.

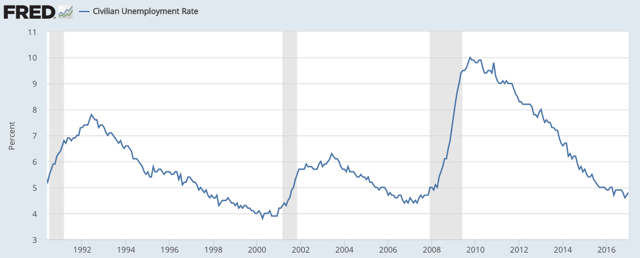

The same type of lagging

phenomenon is seen with unemployment, where companies don't begin

rehiring until they're absolutely certain the economy is continuing on

an upward trajectory. Consequently, unemployment always spikes after

a recession rather than during. This explains why U-3 unemployment

peaked in October 2009 at 10%, and didn't fall below 8% until September

2012, a full four years after the worst of the recession, when

unemployment in the fall of 2008 was only 6.1%.

(Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics; modeled by fred.stlouisfed.org)

2. Low interest rates

This

is a no-brainer with its effect in calculating the value of a business,

which is the amount of cash that can be taken from it over its life

discounted back to the present. The cost of capital is used as the

discount rate. The cost of debt (a portion of the cost of capital) is

lower with lower rates, and is tax deductible assuming the business is

profitable and pays taxes. This compresses discount rates and boosts

corporate valuations even if the numerator term - cash flows, of which a

large portion is earnings - stays constant.

Each

100-bp reduction in the cost of debt projects to increase corporate

valuations by 5%-6%, based on the current financial and capital profile

of the overall US equities market. If cheaper debt also creates the

incentive to take on more debt as a portion of the overall capital

structure, the valuation increase could be even higher assuming the

accretive effects of the relative cheapness of the capital source offset

the additional insolvency risk.

3. Quantitative easing ("QE")

Another

no-brainer, but fundamentally important. Quantitative easing works

through a mechanism by which cash is printed and a central bank uses

that cash to buy a bond or other form of security. This bids down yields

in those assets by reducing their supply in the market and forces

market participants out over the risk curve into riskier assets, such as

stocks and real estate, in order to chase the higher returns of these

assets. This bids up their prices and expects to create a windfall of

wealth that will in turn be spent in the economy in order to drive

growth.

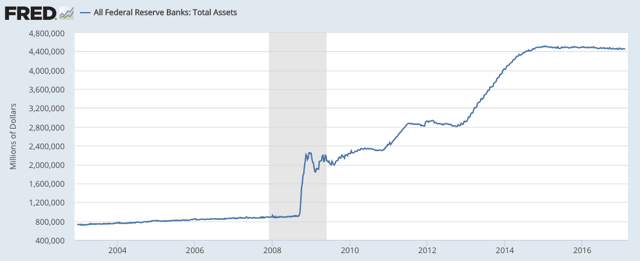

The US Federal Reserve

expanded its balance sheet from $910 billion as of August 2008 (before

the fall of Lehman) to $4.5 trillion as of December 2014, a factor of

5x, where it's mostly stayed since.

(Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System; modeled by fred.stlouisfed.org)

A lot of this QE money fed itself into the stock market. The S&P 500 alone recently zoomed past the $20 trillion market capitalization threshold.

One

could argue that central bank policies are socially non-optimal in that

they reward those who are well off (people who have the ability to buy

stocks and/or real estate) at the expense of those who are savers

(retirees, conservative investors) - who now make little to nothing off

interest - and those unable to invest in risky assets due to a lack of

disposable income. Widening income disparity can breed social conflict

and could be at least be partially attributed to the surprising

electoral outcomes of Brexit, Trump, and possibly additional

unanticipated results in the upcoming European presidential elections in

France, Germany, the Netherlands, and potentially Italy.

(...)

No comments:

Post a Comment