A while ago I proposed to form a new G24, not of nations but of individuals. Such a G24 could contribute to a better world, I thought. The G24 I envisioned would be a group that created ideas (and lobbied for them) in the interest of the world community rather than companies or power groups within countries.

I received a few enthusiastic responses but the G24 I had in mind was not established. That

is not surprising, perhaps, because it is unrealistic to think that you

can create a global think group without a budget.

Thirty

years ago I managed to form precisely such an international group, the

Forum on Debt and Development (FONDAD). But then I received core funding from the Dutch

Ministry of Foreign Affairs. As a network and research center FONDAD still exists, and I am still its director. Since May 2008 FONDAD has operated without a budget. In fact I have been working for FONDAD more than eight years without being paid for it. This proves that it is possible to constitute, or rather continue, an international group without a budget. So could a G24 still be formed, building on members of the FONDAD network and including a few more thinkers with additional expertise (see below)?

My proposal was and is that we create a network of 24 persons to exchange ideas about possible improvements in the global system. Yeah, I know that all kinds of groups and organizations are doing that. My point is, that the G24 I envisage - which might better be

called G25 to avoid confusion with the existing G24 - gives an extra boost,

both intellectual and practical.

For me, the G25 would consist of 25 creative thinkers who are experts in

the fields of politics and economics, socio-economic issues (including

working conditions, unemployment, exclusion and income distribution), environment /

ecology, and (maritime) transport. Why maritime transport? Because 90% of world trade goes via maritime transport. (And because I'm writing a book about world ports, together with my wife Aafke Steenhuis -- who besides being a writer is also a painter; she made the drawings on the cover of the two FONDAD books exposed.)

Profile

To which profile must comply G25 members? I thought of the following:

- You are curious, creative

- You can listen to someone else

- You speak at least two international languages (unfortunately these are European languages, unless you would like to include eg Russian, Chinese or Mandingo), besides English preferably also Spanish, French or Portuguese (see, eg, Global financial experts must understand French... and Global financial experts must play music...)

- You are a non-conformist (see, eg, Robert Triffin: "Most economists are demagogues").

I created FONDAD in 1986 when I was 38 years old. Now I'm 68 and soon will be 69. The G25 should consist of members whose ages range between, say, 25 and 85 years. Members are not expected to do anything else than occasionally contribute to the virtual discussion among G25 members. Examples of how I organised such virtual discussions in the past for members of the FONDAD network are:

Macro-prudential regulation

Bill White: "The current financial system is inadequate

Three schools of thought on crisis prevention

Asset Bubbles and Inflation

Managing the crisis (1)

Preventing the crisis (4)

Explaining the crisis (3)

Explaining the crisis (1)

I continued to moderate such discussions until last year but did not make them any longer public via this blog. If I would restart those discussions involvng people with the additional expertise I just mentioned, I don't intend to spend too much time on moderating the group, publishing its discussions and promoting its policy suggestions. Maybe someone else could do that. I am just too busy -- as are the people I'd like to involve. I'm afraid others will think the same and -- with rare exceptions -- would react by saying: It's a nice idea Jan Joost but, unfortunately, I won't have the time for participating. I would fully understand such reaction and therefore think a G25 will not emerge. However, I keep dreaming that maybe one day, before I am 85...

Saturday, December 24, 2016

Monday, December 19, 2016

Christine Lagarde was found guilty

December 19, 2016

NYTimes.com » |

Breaking News Alert |

|

BREAKING NEWS |

| The chief of the I.M.F. has been convicted of criminal charges. Christine Lagarde may be forced from her post and faces jail time. |

Monday, December 19, 2016 9:20 AM EST |

| Christine Lagarde, the managing director of the International Monetary Fund, was found guilty on Monday of criminal charges linked to the misuse of public funds during her time as France’s finance minister, a verdict that could force her out of her post. |

| Ms. Lagarde, who began her second five-year term at the I.M.F. in February, faces a fine of up to 15,000 euros, or $15,700, and up to one year in jail. The scandal has overshadowed her work at the fund, to which she was appointed in 2011, after Dominique Strauss-Kahn resigned as managing director when he was accused of having sexually assaulted a maid in a New York City hotel. |

| Read more » |

Sunday, December 18, 2016

European integration enters terminal crisis?

|

| Paulo Nogueira Batista, vice president of the New Development Bank |

He sees highly polarized populations in Europe, as well as in the Middle East, Latin America and the United States.

In the developed world the polarization is a reaction to neoliberal globalisation, he observes. And in the US a man like Trump would not have been chosen in more normal circumstances.

So we are living in exceptional times. Do you agree?

Polarização

No Brasil, estamos vivendo regressão fenomenal em termos políticos, institucionais, e até em termos de comportamento

Não sei se os brasileiros se dão conta, mas vários dos nossos problemas estão ocorrendo simultaneamente em diferentes partes do mundo. A crise não é só nossa. Se isso for verdade, ficamos, por um lado, psicologicamente reconfortados. Mas, por outro lado, é mais difícil sair do pântano, uma vez que os problemas econômicos e políticos de outros países rebatem sobre o Brasil, dificultando a superação da nossa crise.

Um traço da crise atual é a polarização da sociedade em vários países ou regiões — EUA, Reino Unido, Europa continental, Turquia, Brasil, Venezuela, por exemplo. Nem falo das guerras civis e da desordem no Oriente Médio — Síria, Líbia, Iraque, Iêmen. Nos países desenvolvidos, a polarização representa uma reação à chamada globalização neoliberal, ou seja, a rejeição do projeto socioeconômico das elites internacionalizadas.

No Brasil, o caso é diferente — o que tivemos, e temos ainda, é a rebelião das elites e da maior parte da classe média contra determinado projeto político e social, que prevaleceu no Brasil de 2003 até 2014. Não pretendo discutir hoje se a rejeição ou rebelião se justifica ou não. Mas queria destacar o quadro de crescente polarização que atinge até mesmo um país como o Brasil, que se notabilizava pela sua capacidade de conciliar divergências.

Nem sempre se observa, leitor, que nas eleições e referendos dos últimos meses a margem das vitórias foi quase sempre pequena. Parece um padrão: Brexit (sair 52%, ficar 48%), eleição de Donald Trump (por 47% a 48% no voto popular — vitória no colégio eleitoral), eleição na Áustria (vitória do candidato verde por 54% contra os 46% do candidato de um partido de extrema-direita).

No Brasil, em 2014, Dilma Rousseff se reelegeu por margem também estreita (52% contra 48%), indicando já então a divisão da sociedade, que seria agravada nos anos seguintes pela campanha pelo impeachment e seus desdobramentos. A exceção foi o referendo na Itália, do- mingo passado, em que a derrota do governo foi por quase 60% a 41%, levando à renúncia do primeiro-ministro do Partido Democrático, de centro-esquerda.

Outro aspecto notável: a disposição do eleitorado de optar por caminhos arriscados. Na Itália parlamentarista, por exemplo, estava claro que a derrota do governo levaria à queda do gabinete e, portanto, a nova eleição, em que a direita nacionalista tem, ao que parece, grande chances de vencer. O Brexit era uma aposta de alto risco para o Reino Unido, como se vê pelas dificuldades que a saída da União Europeia acarreta e continuará a acarretar.

Nos EUA, em situação mais normal, dificilmente um Trump conseguiria se eleger presidente — ou mesmo chegar a ser candidato por um dos dois principais partidos. No Brasil, grande parte da classe média saiu às ruas para pedir a derrubada da presidente eleita, ignorando ou desprezando os vários tipos de riscos que o impeachment estava tendo e continuaria a ter para o país. A violência crescente da disputa política é mais um aspecto que salta aos olhos.

No Brasil, estamos vivendo regressão fenomenal em termos políticos, institucionais, e até em termos de comportamento. Mas não só aqui: a regressão é evidente também nos EUA — muito antes da eleição de novembro — e na Europa onde o projeto “iluminista” de integração regional profunda patina há vários anos, e entrou agora em crise talvez terminal. O espaço acabou. Tento retomar noutra ocasião.

Wednesday, December 14, 2016

FONDAD and the US Debt Problem

Images of a trip to Antwerp mixed with the voices of Barry Eichengreen (University of California) and Jan Joost Teunissen recorded at a FONDAD conference focusing on the US debt problem. The conference resulted in two books:

Global Imbalances and the US Debt Problem: Should Developing Countries Support the US Dollar?

Global Imbalances and the US Debt Problem: Should Developing Countries Support the US Dollar?and Global Imbalances and Developing Countries: Remedies for a Failing International Financial System.

Tuesday, December 13, 2016

Did Christine Lagarde commit a crime?

|

| Christine Lagarde in the court room. |

IMF top woman Christine Lagarde has said on the first day of the trial about an issue from 2008 that the whole affair is based on a series of fabrications. It is suspected that she has intervened in her time as Minister of Finance in a compensation scheme for the French businessman Bernard Tapie.

Tapie received 400 million euros from the state-owned bank Credit Lyonnais after a dispute over the sale of its majority stake in Germany's Adidas.

Lagarde told the Court of Justice of the Republic that she was shocked by the indictment. Which according to her is short-sighted and "a fantasy conspiracy" written by someone who has never met her.

The proceedings against Lagarde will take ten days.

Friday, December 9, 2016

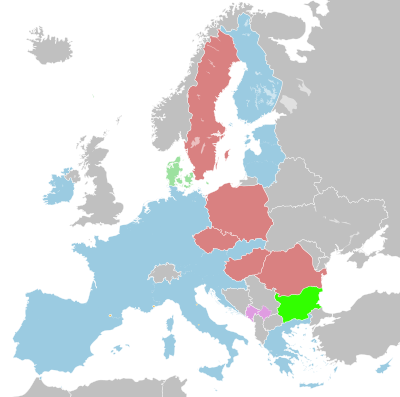

Will EU countries abandon the Euro? (1)

|

| Eurozone, or euro area (in blue). |

In 1998 I voiced my concern about the euro in a Fondad book, Regional Integration and Multilateral Cooperation in the Global Economy (1998), in which I said that I saw a major problem with an unbridled process of ever-deepening regional integration. "How far should it go? Isn't Europe's energetic embracing of a single currency, the Euro, now showing the pitfalls of integration that has gone too fast or too far? Should European nations not put more energy in keeping alive their rich variety of differences - in cultural, social, political and even economic life - rather than almost blindly following the new dogma of 'conversion' of economic policies? ... regional integration should never become a dogma. It is a useful and attractive project as long as those who are intended to benefit from it indeed reap the fruits. ... But on the day that citizens begin to raise serious and well-founded doubts about the supposed beneficial effects, policymakers and entrepreneurs should begin to rethink the wisdom of ever-increasing regional integration. In my view, regional integration should never become an end in itself, but it should be subdued to the broader and 'higher' goals of justice, social equality, cultural identity and respect for nature. In other words, social, political and cultural (and economic!) considerations can be good reasons for a revision of integration plans."

One of the dire consequences of the adoption of the euro was that the Member States of the eurozone (the official name is euro area) no longer had the freedom to implement the political, social and economic policies that their residents wanted. The Maastricht Treaty (1992) convergence criteria or conditions for entering the eurozone meant that a country had to subscribe to a whole set of neoliberal policies and keep its public debt and deficit and inflation at low levels. With these conditions the Maastricht Treaty legitimized and pushed for the austerity policies that since 2010 have been adopted in eurozone countries. Anyone who did not obey and wanted to pursue different policies was threatened with punishment.

The 'convergence' agenda of policies that member countries had to implement, and the establishment of the Eurogroup, ie the group of countries that have adopted the euro, meant in practice that member states had to follow neoliberal policies, even though this has never been explicitly mentioned. Other policies were simply not tolerated.

But, as has happened with the tough prescriptions by the IMF, the powerful countries can always disregard the Maastricht criteria when they think this is in their interest. Germany (after unification with Eastern Germany) and France are examples of poweful countries that broke the Maastricht budget deficit rule. Greece is an example of a weak country that could not escape from the straitjacket of the Maastricht Treaty and the neoliberal consensus of the Eurogroup (of which Greece is a part). When the Tsipras government in 2015 wanted to negotiate a debt deal with the Eurogroup and the ECB (and the IMF), it was simply told that its efforts to end austerity and get debt relief were meaningless as it just had to stick to the euro rules and the debt agreements made by previous governments.

Now that the disastrous consequences of the euro have become visible to more people than just the small group of expert critics, there is increasing doubt about the beneficence of the euro. In several countries voices have called for the abolition or reduction of the role of the euro, and the reintroduction of a national currency.

Right-wing populist leaders like Marine Le Pen and Geert Wilders have capitalized on the discomfort over austerity measures. They have announced that they will abandon the euro in their countries if they have the power to do so. Because the National Front of Le Pen in France and the Freedom Party of Wilders in the Netherlands do well in the elections and the polls, receiving more votes than any other party, the European technocrats defending the euro are concerned. They are feverishly searching for ways to prop up the European common currency. Their fear is that if one country leaves the eurozone, others might follow.

Ideas of how Europe could maintain the euro range from restricting it to a number of countries in northern Europe to democratizing the Eurogroup and giving its member states more freedom to implement the policies they see as fit.

There are also those who advocate reintroducing a national currency while preserving the euro as an international means of payment, just like the dollar. Is a breakup of the eurozone possible?

In a paper about the dismantling of the euro, "The Breakup of the Euro Area", the economist Barry Eichengreen, who has studied for many years the European monetary system and the international monetary system and has contributed to Fondad conferences and books, wrote in July 2007 that a country that abandons the euro and reintroduces a national currency might face major technical difficulties. But it can do it. One of the countries that might decide to leave the euro area was Portugal, he said, and another Germany:

"Different countries could abandon the euro for different reasons. One can imagine a country like Portugal, suffering from high labor costs and chronic slow growth, reintroducing the escudo in the effort to engineer a sharp real depreciation and export its way back to full employment. Alternatively, one can imagine a country like Germany, upset that the ECB has come under pressure from governments to relax its commitment to price stability, reintroducing the deutschemark in order to avoid excessive inflation."

A country where plans were made to withdraw from the eurozone and reintroduce the national currency was Greece. Are there similar plans in other countries?

to be continued (and revised)

Monday, December 5, 2016

Is Europe run jointly by its technocrats and CEOs?

|

| European Round Table of Industrialists (ERT) meeting Merkel, Hollande and Juncker. |

All multinationals mentioned, except Maersk, are currently member of the powerful business lobby group European Round Table of Industrialists (ERT). Observers say that ERT was the major force behind the creation of the euro and the attempt to get TTIP adopted.

On its website the ERT says it is "a forum bringing together around 50 Chief Executives and Chairmen of major multinational companies of European parentage covering a wide range of industrial and technological sectors. Companies of ERT Members are widely situated across Europe, with combined revenues exceeding € 2,135 billion, sustaining around 6.8 million jobs in the region. They invest more than € 55 billion annually in R&D, largely in Europe."

According to the Dutch version of Wikipedia, the ERT can be considered as one of the main architects of the great treaties of the European Union [1] since 1985, and policy decisions such as the EU enlargement, the introduction of the euro, pan-European connections such as Eurotunnel and the Oresund Bridge between Denmark and Sweden, [2] the Lisbon Strategy [3] or the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership TTIP. [4]

The English version of Wikipedia says that "The political agenda of the EC [EU] has to a large extent been dominated by the ERT......While the approximately 5000 lobbyists working in Brussels might occasionally succeed in changing details in directives, the ERT has in many cases been setting the agenda for and deciding the content of EC [EU] proposals."[3] quoting Keith Richardson's study Big Business and the European Agenda (2000), The Sussex European Institute, p.30.

Other European companies setting the policies of governments include big bankers. Insiders once told me that Angela Merkel followed the advice of Josef Ackermann when he was still the CEO of Deutsche Bank. An article in the NYT confirms Ackermann's influence on Merkel, Deutsche Bank's Chief Casts a Long Shadow in Europe.

Sunday, December 4, 2016

Is China the largest economy? A historic exchange with Mohamed El-Erian

|

| Mohamed El-Erian |

Sure, you may also look at and try to understand the political and cultural climate we are living in now. But in this post I will only look at the GDP figures of the 10 largest countries in terms of their GDP.

Below is an article that tells us what are the 10 largest economies at this moment, and what countries are likely to be at the top in four or more years. The country figures are presented with a few observations by the author, Prableen Bajpai.

I will conclude this long post at the bottom with an exchange I once had with Mohamed El-Erian.

The World's Top 10 Economies

By Prableen Bajpai, CFA (ICFAI) | Updated July 18, 2016

When it comes to the top 10 national economies around the globe, the order may shift a bit, but the key players usually remain the same, and so does the name at the head of the list. The United States has been the world’s biggest economy since 1871. But that top ranking is now under threat from China.

Will It Even Matter?

Only for bragging rights! With a population less than one-fourth that of China, the U.S. is still projected to remain one of the world’s most prosperous economies, and still the far ahead in terms of per capita GDP, which reflects living standards and quality of life for a nation’s residents. Even so, it throws an interesting light on the whole subject of GDP and global economies.

Why Is GDP Important?

The GDP of a country provides a measure of the total monetary value of all the goods and services it produces during a certain time period, most commonly a year. This is an important statistic that indicates whether an economy or growing or contracting. In the United States, the government releases an annualized GDP estimate for each quarter and also for an entire year; it makes a preliminary estimate, based on the initial information it has, and then makes a second estimate and a final one as more information flows in.

A country's GDP is essentially a measure of the health and size of its economy. Countries with healthy economies tend to produce more goods and have higher GDPs, and could therefore be said to be the most productive. A growing GDP represents expansion within a country's economy, signaling that it is in the process of becoming more productive.

Providing a quantitative figure for GDP helps a government make decisions such as whether to stimulate the economy by pumping money into it, in case the economy is not growing and needs such stimulus. And in case the economy is getting heated, a government could also act to prevent it from getting overheated. The US government, for example, makes

Businesses can also use GDP as a guide to decide how best to expand or contract their production and other business activities. And investors also watch GDP since it provides a framework for investment decision-making.

Types of GDP

There are different ways to calculate GDP. Nominal GDP is the total value of all the finished goods and services produced within a country’s borders in a specific time period, evaluated at current market prices in its local currency. But GDP can also be calculated based on purchasing power parity (PPP), which is essentially the implied exchange rate at which the currency of one country would have to be converted into that of another country to buy an identical basket of goods and services in each. One of the best-known examples of PPP is the “Big Mac” index, published by The Economist magazine, which calculates simplified PPP exchange rates based on the popular McDonald’s sandwich. The biggest advantages of PPP exchange rates is that they have greater stability over time as compared to more volatile market exchange rates, and they provide a better estimate of consumers’ purchasing power in developing nations.

As a general rule, developed countries have a smaller gap between their nominal GDP (i.e., current prices) and GDP based on PPP. The difference is greater in developing countries, which tend to have a higher GDP when valued on purchasing power parity basis.

Another method of analyzing a country's productivity is by calculating its GDP per capita, which is accomplished by simply dividing its GDP by its population. This gives an indication of how productive, on average, each citizen is.

The Top 10 Economies in the World

Note: This list is based on IMF’s World Economic Outlook Database, October 2016. Select data is from the CIA World Factbook.

United States

The U.S. economy remains the largest in the world in terms of nominal GDP. The $18.5 trillion U.S. economy is approximately 24.5% of the gross world product. The United States is an economic superpower that is highly advanced in terms of technology and infrastructure and has abundant natural resources. However, the U.S. economy loses its spot as the number one economy to China when measured in terms of GDP based on PPP. In these terms, China’s GDP is $21.3 trillion and the U.S. GDP is $18.5 trillion. However, the U.S. is way ahead of China in terms of GDP per capita (PPP) – approximately $57,294 in the U.S. versus $15,423 in China.

China

China has transformed itself from a centrally planned closed economy in the 1970s to a manufacturing and exporting hub over the years. The Chinese economy overtook the U.S. economy in terms of GDP based on PPP. However, the difference between the economies in terms of nominal GDP remains large with China's $11.3 trillion economy. The Chinese economy has long been known for its strong growth, a growth of over 7% even in recent years. However, the country saw its exports projected to grow only by 1.9% in 2016, and total GDP growth has gone down to 6.5% and is projected to slow to 5.8% by 2021. The country's economy is propelled by an equal contribution from manufacturing and services (45% each, approximately) with a 10% contribution by the agricultural sector.

Japan

Japan’s economy currently ranks third in terms of nominal GDP, while it slips to fourth spot when comparing the GDP by purchasing power parity. The economy has been facing hard times since 2008, when it was first showed recessionary symptoms. Unconventional stimulus packages and combined with subzero bond yields and weak currency have further strained the economy (for related reading, see: Japan's economy continues to challenge Abenomics). Economic growth is once again positive, to just over 0.5% in 2016; however it is forecasted to stay well below 1% during the next six years. The nominal GDP of Japan is $4.73 trillion, its GDP (PPP) is $4.93 trillion, and its GDP (PPP) per capita is $38,893.

Germany

Germany is Europe’s largest and strongest economy. On the world scale, it now ranks as the fourth largest economy in terms of nominal GDP. Germany’s economy is known for its exports of machinery, vehicles, household equipment, and chemicals. Germany has a skilled labor force, but the economy is facing countless of challenges in the coming years ranging from Brexit, the greek debt crisis to the refugee crisis (for related reading, see: 3 economical challenges Germany faces in 2016). The size of its nominal GDP is $3.49 trillion, while its GDP in terms of purchasing power parity is $3.97 trillion. Germany’s GDP (PPP) per capita is $48,189, and the economy has moved at a moderate pace of 1-2% in recent years and is forecasted to stay that way.

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom, with a $2.65 trillion GDP, is currently the world’s fifth largest. Its GDP in terms of PPP per capita is $42,513. The economy of the UK is primarily driven by services, as the sector contributes more than 75% of the GDP. With agriculture contributing a minimal 1%, manufacturing is the second most important contributor to GDP. Although agriculture is not a major contributor to GDP, 60% of the U.K.’s food needs is produced domestically, even though less than 2% of its labor force is employed in the sector. After the referendum in June 2016 when voters decided to leave the European Union, economic prospects for the UK are highly uncertain, and the UK and France may swap places. The country will operate under EU regulations and trade agreements for two years after the formal announcement of an exit to the European Council, in which time officials will work on a new trade agreement. Economists have estimated that Brexit could result in a loss of anywhere from 2.2-9.5% of GDP long term, depending on the trade agreements replacing the current single market structure. The IMF, however, projects growth to stay between 1.05-1.09% in the next five years.

France

France, the most visited country in the world, today has the sixth largest economy with a nominal GDP of $2.48 trillion. Its GDP in terms of purchasing power parity is around $2.73 trillion. France has a low poverty rate and high standard of living, which is reflected in its GDP (PPP) per capita of $42,384. The country is among the top exporters and importers in the world. France has experienced a slowdown over the past few years and the government is under immense pressure to rekindle the economy, as well as combat high unemployment which stood at 9.8% in 2016 (a slight drop from 10.35% in 2015). According to IMF forecasts the country's GDP growth rate is expected to rise over the next five years, and unemployment is expected to continue to go down.

India

India ranks third in GDP in terms of purchasing power parity at $8.7 trillion, while its nominal GDP puts it in a seventh place with $2.25 trillion. The country’s high population drags its GDP (PPP) per capita down to $6,658. India’s GDP is still highly dependent on agriculture (17%), compared to western countries. However, the services sector has picked up in recent years and now accounts for 57% of the GDP, while industry contributes 26%. The economy’s strength lies in a limited dependence on exports, high saving rates, favorable demographics, and a rising middle class. India recently overtook China as the fastest growing large economy.

Italy

Italy’s $1.8 trillion economy is as of this writing the world’s eighth largest in terms of nominal GDP. Italy is among the prominent economies of the Eurozone, but it has been impacted by the debt crisis in the region. The economy suffers from a huge public debt estimated to be about 133% of GDP, and its banking system is close to a collapse and in need of a bailout/bail-in. The economy is also facing high unemployment, but saw a positive economic growth in 2015 for the first time since 2011, which is projected to continue. The government is working on various measures to boost the economy that has contracted in recent years. The GDP measured in purchasing power parity for the economy is estimated at $2.22 trillion, while its per capita GDP (PPP) is $36,313.

Brazil

With its $1.77 trillion economy, Brazil now ranks as the ninth largest economy by nominal GDP. The Brazilian economy has developed services, manufacturing, and agricultural sectors with each sector contributing around 68%, 26%, and 6% respectively. Brazil is one of the BRIC countries, and was projected to continue to be one of the fastest growing economies in the world. However, the recession in 2015 caused Brazil to go from seventh to ninth place in the world economies ranking, with a negative growth rate of 3.2%. The IMF does not expect positive growth until 2017, and the unemployment rate is expected to grow to over 11% during the same time period before it declines again. The Brazilian GDP measured in purchasing power parity is $3.1 trillion, while its GDP per capita (PPP) is $15,211.

Canada

Canada has recently pushed Russia off the top 10 list with a nominal GDP of $1.53 trillion. Canada has a highly service oriented economy, and has had solid growth in manufacturing as well as in the oil and petroleum sector since the Second World War. However, the country is very exposed to commodity prices, and the drop in oil prices kept the economy from growing more than 1.2% in 2015 (down from 2.5% in 2014). The GDP measured in purchasing-power parity is $1.7trillion, and the GDP per capita (PPP) is $46,239.

The nominal GDP of the top 10 economies adds up to over 66% of the world’s economy, and the top 15 economies add up to over 75%. The remaining 172 countries constitute only 25% of the world’s economy.

And Looking Forward …

Some other economies that are a part of the “trillion-dollar” club and have the potential to make it to the top 10 going ahead are South Korea ($1.4 trillion), Russia ($1.26 trillion), Australia ($1.25 trillion), Spain ($1.25 trillion), and Mexico ($1.06 trillion).

By the year 2020, a great shift will

have occurred in the worldwide balance of economic power. Most of the

economies in the current top 10 list are developed countries in the

western world. But analysts predict emerging market economies will become some of the most important forces in the next few years.

The Top Economies of 2021

The rising importance of emerging market

economies in 2021 will have broad implications for the world’s

allocation of consumption, investments and environmental resources. Vast

consumer markets in the primary emerging market economies will provide

domestic and international businesses with many opportunities. Although

income per capita will remain the highest in the world's developed

economies, the growth rate in per capita income will be much higher in

major emerging market nations such as China and India.

According to projected nominal GDP, the top economies in 2021

will be China, the U.S., India, Japan, Germany, Russia, Indonesia,

Brazil, the U.K. and France respectively. One of the major reasons for

the growth of emerging economies is that advanced economies are mature

markets that are slowing. Since the 1990s, the economies of advanced

countries have experienced far slower growth in comparison to the rapid

growth of emerging economies such as India and China. The worldwide

financial crisis from 2008 to 2009 fueled the trend of decline among the

advanced economies.

For example, in 2000 the U.S., the

number one economy in the world, accounted for 24% of the world's total

GDP. This declined to just over 20% in 2010. The financial crisis and a

faster-paced growth by emerging economies were key factors in the

decline of the U.S. economy in relation to China. In the mid-2000s,

Japan’s economy saw a slight recovery after a lengthy period of

inactivity that was due, at least in part, to inefficient investments

and to the burst of the asset price bubbles. The global economic

downturn has had a significant impact on the country because of

prolonged deflation and the country’s heavy dependence on trade.

The economies of countries in the

European Union, which include France, Italy and Germany, account for

just over 20% of the world’s total GDP. This is a relatively large

decrease from the year 2000, when these countries collectively held over

25% of the world’s GDP. The increase in average population age and

rising unemployment rates is contributing to this slowdown.

Before the Brexit vote in late June 2016, the IMF issued a report warning the UK of the economical consequences of leaving the EU. Brexit

aside, the IMF predicts advanced economies will experience a growth of

less than 3% in 2020. Advanced economies are also facing challenges in

terms of public debt reduction and government budget deficits. The IMF

also forecasts that growth of Asian economies will be significantly

higher, at approximately 9.5%, and it is one of the factors driving the

worldwide economic recovery.

The Advance of Emerging Countries

Emerging economies are catching up with

the progress of the advanced world and are predicted to overtake many of

them by 2020. This will cause a substantial shift in the global balance

of economic power. China’s share of the world’s total GDP increased

more than 6% from 2000 to 2010. As already noted, by some calculations,

China is already ranked as the largest economy in the world.

Many analysts foresee India surging in

growth and taking over Japan’s place as the third largest economy in the

world by 2020. Some believe India may grow even more rapidly and push

the U.S. into third place. Analysts point out India’s young and

faster-growing population as key factors in the rate of growth for this

country’s economy.

Russian and Brazilian growth potential

is great, as both countries are two of the world’s largest exporters of

natural resources and energy. However, in the future, the lack of

economic diversification in Russia may be likely to cause the country

some difficulty with continued growth.

Analysts also expect that by 2020,

Mexico will have the 10th largest economy by GDP measured at PPP terms.

The country’s proximity to the U.S., growing business and trade deals

with the U.S. and a growing population will aid its economic

development.

Implications of the Economic Shift

As household incomes rise and populations expand, the service and consumer goods

markets will present exponential opportunities in emerging markets.

More specifically, luxury goods will have opportunities in these markets

as more families reach the middle class.

One of the biggest implications is the

importance placed on younger consumers. Though in some emerging

countries, including China, the population is aging, the populations of

emerging markets are overall significantly younger than those of people

in advanced economies. Young consumers also represent substantial power

over purchases, particularly large items such as cars and homes, as well

as the items needed to furnish homes.

Emerging countries are likely to become

important foreign investors. The foreign investments they are

responsible for making only serve to enhance their influence in the

global economy. Investments from foreign countries, including those from

advanced nations, will also flow more readily into these developing

nations, further driving their economies toward future growth.

Exchange with Mohamed El-Erian

|

| Mohamed El-Erian |

The reason I put a picture of Mohamed El-Erian at the top of this post is that his picture appeared at the top of the article copied above, in a video. I got to know Mohamed in 1992 when he participated for the first time in a FONDAD conference I had organised and of which I made the book Fragile Finance: Rethinking the International Monetary System.

Mohamed El-Erian has participated in many FONDAD conferences, and very much wanted to participate in a 2-day international workshop on "Unfettered finance is fast reshaping the global economy", I proposed in June 2007.

This is what I wrote to Mohamed El-Erian and other experts I invited on June 24, 2007:

Dear friends, Martin Wolf has written a highly interesting analysis, "Unfettered finance is fast reshaping the global economy", in FT of 18 June (attached). I think it is a topic worth analysing further in a 2-day workshop with a view to providing a profound analysis and, equally or even more challenging, presenting possible policy responses. My proposal is to hold such a workshop in the period of 4 to12 December 2007 in Santiago de Chile at either Cepal (ECLAC) or the Banco Central de Chile. I hope that this will be a convenient period for you and that either Cepal or the Banco Central will be able to host the meeting. Martin Wolf's article prompts analysis and policy responses on four issues: 1. WHAT ARE THE PROBLEMATIC CONSEQUENCES? Given "the transformation of mid-20th century managerial capitalism into global financial capitalism" and "the triumph of the speculator over the manager and of the financier over the producer" (Wolf's words) -- exemplified by the explosion of interest rate swaps, currency swaps and interest rate options reaching $286,000 billion by the end of 2006 (about six times global gross product), the boom of hedge funds managing about $1,600 billion, and the vast size of the new private equity funds and the scale of bond financing by banks making even the largest and most established companies candidates for sale and break-up -- what have been and will be the problematic consequences of this vast expansion in financial activity? 2. WHAT ARE THE REGULATORY CHALLENGES? Given the liberalisation of the global financial sector, and given that "low interest rates and the accumulation of liquid assets, not least by central banks around the world, have fuelled financial engineering and leverage" (Wolf's words), what can financial authorities (ministries of finance, central banks, regional and international financial institutions) do to reduce, turn back and prevent the negative consequences? Wolf observes, "regulating a system that is this complex and global is a novel task for what are still predominantly national regulators." 3. WHAT ARE THE SOCIAL AND POLITICAL CHALLENGES? Martin Wolf observes: "Powerful political coalitions are forming to curb the impact of the new players and new markets: trade unions, incumbent managers, national politicians and hundreds of millions of ordinary people feel threatened by a profit-seeking machine viewed as remote and inhuman, if not inhumane." "Financial speculators earn billions of dollars, not over a lifetime but in a single year. Such outcomes raise political questions in most societies. ... Democratic politics, which gives power to the majority, is sure to react against the new concentrations of wealth and income. Many countries will continue to resist the free play of financial capitalism. Others will allow it to operate only in close conjunction with powerful domestic interests. Most countries will look for ways to tame its consequences. All will remain concerned about the possibility for serious instability." 4. IS A COHERENT VISION ON GLOBAL FINANCIAL CAPITALISM POSSIBLE? Martin Wolf observes that we are witnessing a new global financial capitalism that creates "vast new regulatory, social and political challenges". Providing ideas to financial policymakers, politicians and citizens of how to address these challenges may be facilitated by presenting a coherent vision on the functioning of global financial capitalism. Is it possible to develop such a vision? On what political and economic premises (ideals) will such a vision and the desired policy responses be based? In addition to these four challenges, there is a fifth challenge: the possibility of another systemic risk episode as a result of abundant global liquidity, the high volume of financial transactions and market volatility. This is a large -- too large -- agenda for a 2-day workshop, but I hope it is a useful starting point for a discussion with you about how to narrow down and draft a more specific agenda -- if you would find my proposal appealing. Given Fondad's mission, we should focus in particular on emerging and developing economies. I suggest to invite a small number of participants (about 20) to enable an in-depth discussion. If all of you (and the others included in my draft list of participants -- see list below) would be interested in participating we already have 22 participants.

And this is what Mohamed El-Erian replied to me:

Thanks very much Jan Joost The topic is an important one and you identify the key issue. I would suggest a greater emphasis on financial infrastructure aspects, including the de facto linkage with domestic markets in developing countries. Needless to say, I would love to participate in such an event. The dates may be a big issue for me. Best

Mohamed

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)